[Download PDF]

Aída Martínez-Gómez

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Goals

This study aims to analyze the initial assumptions about and attitudes toward interpreting by heritage language learners who have experience as informal interpreters (e.g., for their families and communities) before they enter a formal undergraduate translation and interpretation program. Its ultimate goal is to contribute to the development of pedagogical methods that capitalize on the strengths that these students already possess and that are sensitive to the needs that emerge from their experiences as family interpreters.

Description of the study

Rationale

Interpreter education has traditionally focused on elective sequential bilinguals (i.e., individuals who grew up as monolinguals and purposefully acquired their L2 after childhood). However, the student body in Spanish interpreting programs in the U.S. is mainly comprised of heritage learners who also have previous experience as language brokers. When these young bilinguals act as interpreters for LEP (limited English proficiency) members of their communities, they not only intuitively develop interpreting skills, but also are affected by the social and emotional relationships that they have with the LEP individuals. This study attempts to incorporate these life experiences to formal curricula.

Methods

- Participants: Three cohorts of students registered in the Spanish BA (Translation and Interpretation concentration) or in the Certificate Programs in Legal Translation and Interpreting at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (n=67)

- Cohort 1 (n=19); Cohort 2 (n=27); Cohort 3 (n=21)

- Data collection instrument: Self-administered online-based questionnaire that included:

- an informed consent form;

- 16 sociodemographic questions;

- the Interpreter Interpersonal Role Inventory (Angelelli 2004), with a total of 38 Likert-scale items about the role of the interpreter;[1] and

- an open space for a narrative where students share their perceptions about their tasks as interpreters through stories or anecdotes (approx. 500 words).

- Data collection timeline

Responses for each cohort were collected during the first two weeks in the first interpreting course required for these academic programs (SPA 231 Interpreting I). This course was offered in fall 2015 (cohort 1), fall 2016 (cohort 2), and fall 2017 (cohort 3).

For the purposes of this study, only parts (b) and (d) from the data collection instrument section above were analyzed:

- Sociodemographic questions: descriptive statistics (quantitative)

- 500-word narratives: thematic analysis (qualitative)

[1] This Inventory includes statements about actual experiences (“During an interpretation I constantly check my position to be neutral”), as well as about underlying perspectives on the interpreter’s role (“It is not my job to try to read the parties’ emotions or re-express them”. Respondents indicate their degree of agreement with each statement on a six-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

Results

Questionnaire (part B of data collection instrument)

- Sociodemographic information

- 80% Female

- 4 years old (mean)

- 55% born abroad:

- Arrived to USA at age 11.4 (mean)

- From 14 different countries of origin/backgrounds:

- 37% Dominican, 19% Ecuadorian, 16% Mexican.

- Informal interpreting experience:

- Started interpreting at age 13.4 (mean)

- For parents (96%), family friends (61%), other relatives (46%)

- Daily (21%) or a few times/week (43%)

- In healthcare (82%), shopping (70%), education (53%), social services (46%)

Narratives (part D of data collection instrument)

Perception of role

Participants see interpreting as part of a set of multiple roles that they (are called to) perform for the well-being of the family/community. They see themselves as assistants, emotional supporters, advocates, etc. In fact, they often claim to be the main “problem solvers” of the family.

Attitudes

Participants expressed mixed feelings about interpreting.

Positive feelings: feelings of accomplishment, joy, pride around two major sources of satisfaction: ability to give back to their community and work towards social justice for individuals made vulnerable because of the language barrier (especially close family members); opportunities for self-improvement regarding their language and interpreting skills.

Negative feelings: feelings of frustration, burden, self-doubt, fear, dispiritedness, etc., associated with the following triggers:

- Demands and expectations from family members

- Self-imposed high standards of performance

- Role reversal within the family structure

- Lack of trust in their abilities/intentions

- Potential negative consequences of their interpreting errors

- Emotionally-loaded situations

- Conflicting responsibilities (interpreting vs. schoolwork)

- Language/interpreting difficulties (see next section)

Assessment of interpreting skills

Features of successful interpretations (commonly associated with positive feelings): Informants felt comfortable and confident in their ability to facilitate successful interlinguistic communication when:

- Matters discussed were basic and easily understandable (e.g., shopping)

- Primary participants supported them to accomplish effective communication:

- Linguistically: lowering register, providing explanations, ensuring interpreters’ understanding

- Conversationally: speaking slowly and in short sentences, providing pauses for interpretation

- Emotionally: making interpreter feel comfortable, showing empathy for language challenges, showing confidence in interpreter’s skills

Main difficulties (commonly associated with negative feelings): Informants encountered problems in the following areas:

- Lack of confidence in language skills

- Particularly troubled by “lack of vocabulary”

- Terminological difficulties: legal, medical

- Difficulties understanding concepts/complex matters

- Difficulties related to interpreting techniques: speed (fast speakers), memory

- Difficulties related to interpersonal factors: conveying emotions, insults/curses

- Lack of collaboration from primary participants: speed, tone, register, politeness, impatience, pressure to deliver

Own lack of impartiality (i.e., judging family members or English speakers)

Implications for interpreter education

Interpreting Competence

Translation (and interpretation) competence is understood as “the underlying system of knowledge, skills and attitudes required to translate” (PACTE Group 2017a: 294). According to the PACTE research group, Translation Competence comprises the following subcompetences:

- Bilingual sub-competence: “Predominantly procedural knowledge required to communicate in two languages. […] It comprises pragmatic, sociolinguistic, textual, grammatical and lexical knowledge in the two languages.”

- Extralinguistic sub-competence. “Predominantly declarative knowledge, compris[ing] bicultural […], encyclopaedic […, and] subject knowledge.”

- Knowledge of Translation sub-competence: “Predominantly declarative knowledge, […] about what translation is and aspects of the profession. It comprises: (1) knowledge about how translation functions: translation units, processes required, methods and procedures used (strategies and techniques), and types of problems; (2) knowledge related to professional translation practice.”

- Instrumental sub-competence. “Predominantly procedural knowledge related to the use of documentation resources and information and communication technologies applied to translation.”

- Strategic sub-competence. “Procedural knowledge to guarantee the efficiency of the translation process and solve problems encountered.”

- Psycho-physiological components. “Different types of cognitive and attitudinal components and psycho-motor mechanisms. They include: (1) cognitive components such as memory, perception, attention and emotion; (2) attitudinal aspects such as intellectual curiosity, perseverance, rigour, critical spirit, knowledge about and confidence in one’s own abilities, the ability to measure one’s own abilities, motivation, etc.; (3) abilities such as creativity, logical reasoning, analysis and synthesis, etc.” (PACTE Group 2017b: 39-40)

According to Angelelli (2002: 25-26), interpreter education must focus on teaching (bilingual and bicultural) interactional competence by ensuring the development of skills in six areas, five of which either overlap or could be included in the sub-competences above:

- Linguistic: it overlaps with bilingual sub-competence.

- Setting: declarative and procedural knowledge of the “different ways of speaking in a variety of discourse communities, as well as the content and terms that are at the core of it”. It overlaps with bilingual and extralinguistic sub-competences.

- Sociocultural: declarative knowledge about “the impact that both institution[s] and society have on the interaction, [… and their] constraints”. It is a specific aspect of the extralinguistic sub-competence.

- Cognitive processing: “specific skills related to the process of interpreting (e.g., active listening, memory expansion, split attention, and note taking).” It overlaps with the cognitive psycho-physiological components, although some aspects (e.g., note taking) could be subsumed under the instrumental sub-competence as a series of abilities specifically related to interpreting (not translation).

- Professional: declarative knowledge of “job ethics, certification processes, and professional associations’ rules and regulations”. It overlaps with knowledge of translation sub-competence

- Interpersonal: declarative and procedural knowledge of “the concept of role”, including understanding of “the continuum of visibility and neutrality” and “awareness of the power they have, their agency, and the responsibilities and duties that arise from it”. This area could be considered a completely different and independent sub-competence that is nonetheless central for interpreting.

Suggestions to incorporate the study findings to interpreting pedagogies

Analyzing the study findings through the lens of Interpreting Competence allows educators to identify the needs of this specific student body and potential ways to make them central to our curricula. The narratives analyzed above showed participants’ particular concern regarding their language skills (both in general and, most notably, in specialized settings), conversation management and various interpersonal matters, all of which can affect them psychologically.

Bilingual sub-competence:

Students need to gain self-confidence in their language skills:

- Educators and peers can act as catalyzers, creating a nonjudgmental environment for language use in the classroom and encouraging positive feedback

- Students develop their language skills from a positive understanding of their already solid foundation, through regular exposure to and practice of both languages.

- Educators and students work together to overcome the fear of “lack of vocabulary”. Educators can guide students through activities focusing on lexical research and acquisition, glossary building, development of lexical availability (e.g., through competitive/interactive classroom activities), etc.

Extralinguistic sub-competence:

Students learn about specialized areas of knowledge and institutional settings:

- Contexts can be selected from the students’ own experiences.

- Educators can encourage and guide the research and acquisition of declarative knowledge on certain areas.

- Peers can act as co-researchers and jointly train other students in their selected areas.

- Strategies for acquisition of specialized terminology can be similar to those presented for the development of bilingual sub-competence.

- These processes also contribute to developing the instrumental sub-competence

Knowledge of Interpreting sub-competence:

Students learn about interpreting and its profession:

- Learning about Interpreting Competence as a broad set of skills may reduce students’ fixation on language skills and perceived vocabulary deficiencies.

- Learning about basic interpreting theory (Gile’s Efforts Model, cognitive studies on expertise and deliberate practice) may reduce anxiety and stress through awareness and active management of the complex cognitive processes involved in interpreting.

- Critical readings about codes of ethics and standards of practice may equip students with tools to react confidently to conflicts. (See further discussion of ethics under Interpersonal subcompetence.)

Interpersonal sub-competence:

The vast majority of conflicts that students report are interpersonal. Students need to strengthen their ability to work with people, build their trust, and react to potential conflict.

- Educators can foster a climate of awareness of and respect for the pressures that students experience from their family members, their sense of responsibility and obligation, and their views on interpersonal relationships in interpreting environments.

- Critical discussions of interpersonal difficulties or conflicts becomes essential for students to process their previous experiences, to analyze the implications of different courses of action, and to extract principles for future problem-solving

- Examples of challenging scenarios can be selected from the students’ own experiences.

- Discussion includes reflection on the expectations of the parties involved in the constraints imposed by the setting.

- Discussion includes the applicability of current codes of ethics to certain contexts and/or specific experiences (and the limitations thereof).

- Readings about interpreting users’ expectations and about the multifaceted role of the interpreter can stimulate discussion.

- Educators and students commit to nonjudgmental analysis and critique of interpreter behaviors in order to ensure that all points of view are shared.

- Educators guide students in the analysis of conversation management roadblocks (speed, interruptions, overlapping talk, lengthy utterances) and in the development of problem-solving strategies for these issues.

Psycho-physiological components

Participants report a conflicted relationship with interpreting, which triggers both positive feelings to the point of considering interpreting as a career and negative feelings to the point of avoiding interpreting situations. Emotional support and relief thus becomes a central part of the curriculum:

- The classroom becomes a space to heighten positive feelings. Students’ drive to fight for linguistic rights and social justice is a powerful motivation.

- Positive feedback from educators and peers contributes to the development of self-confidence.

- Work on the above-mentioned sub-competences may reduce the negative feelings related to experienced difficulties.

- The classroom becomes a safe environment to share negative feelings.

- Students can engage in individual journaling to process feelings and anxieties (to be shared or not with instructors and peers)

- If possible and available, educators can work together with the school’s Counseling Center, encouraging students to use their service and enlisting the professionals’ participation in certain classes or activities.

- Readings on vicarious trauma in interpreters can be used to encourage discussion regarding coping with emotional information shared during interpretations

- Educators offer debriefing opportunities for both simulated activities in the classroom (see Strategic sub-competence below) and for actual experiences outside the classroom.

- Students get used to check with themselves after an assignment and analyze and process feelings and emotions that may emerge.

- Students create an maintain peer-support networks reaching beyond the classroom

- The degree of instructor’s guidance and participation depends on the preferences of each specific group of students and may range from sharing the idea and encouraging the creation of these networks to more active participation and direct support.

Strategic sub-competence:

All the sub-competences listed above are developed and strengthened jointly through specific interpreting practice and self-reflection:

- Students’ real interpreting experiences can be reflected through role-plays in the safe environment of the classroom

- Practice in the community (through volunteering or internships) provides real experiential learning opportunities

- The nature and intensity of mentor supervision can be controlled depending on the readiness level of students

- In both types of activities, exposure to increasingly complex interpreting scenarios can be controlled depending on the readiness level of students

- These activities serve as powerful discussion tools regarding decision-making processes, interpreting behaviors and students’ attitudes.

References

Angelelli, C. (2002). Designing curriculum for healthcare interpreter education: A principles approach. In C. Roy (Ed.), New approaches to interpreter education (pp. 23-46). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Angelelli, C. (2004). Revisiting the interpreter’s role. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Gile, D. (1995). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

PACTE Group. (2017a). Conclusions: Defining features of Translation Competence. In A. Hurtado Albir (Ed.), Researching Translation Competence by PACTE Group (pp. 281-302). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

PACTE Group. (2017b). PACTE Translation Competence model: A holistic, dynamic model of Translation Competence. In A. Hurtado Albir (Ed.), Researching Translation Competence by PACTE Group (pp. 35-41). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Please cite as: “Reshaping language interpreting pedagogy through students’ self-perception of their role as ad hoc interpreters,” (2018) New York, NY: Aída Martínez-Gómez. Retrieved from: https://iletc.commons.gc.cuny.edu/reshaping-language-interpreting-pedagogy

Materials developed with financial support from ILETC.

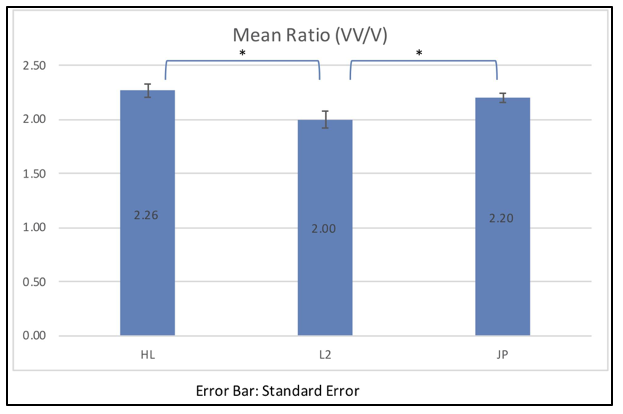

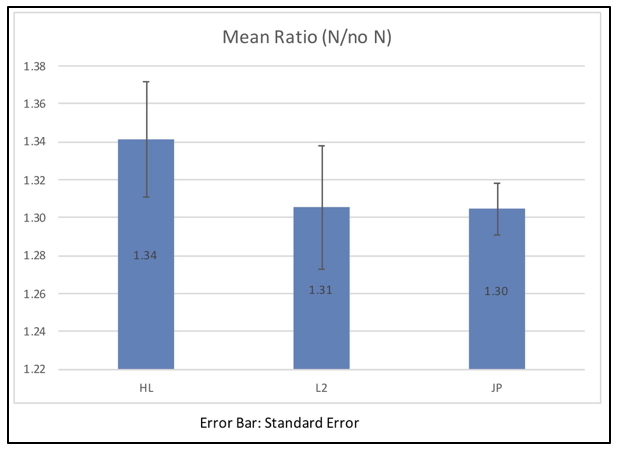

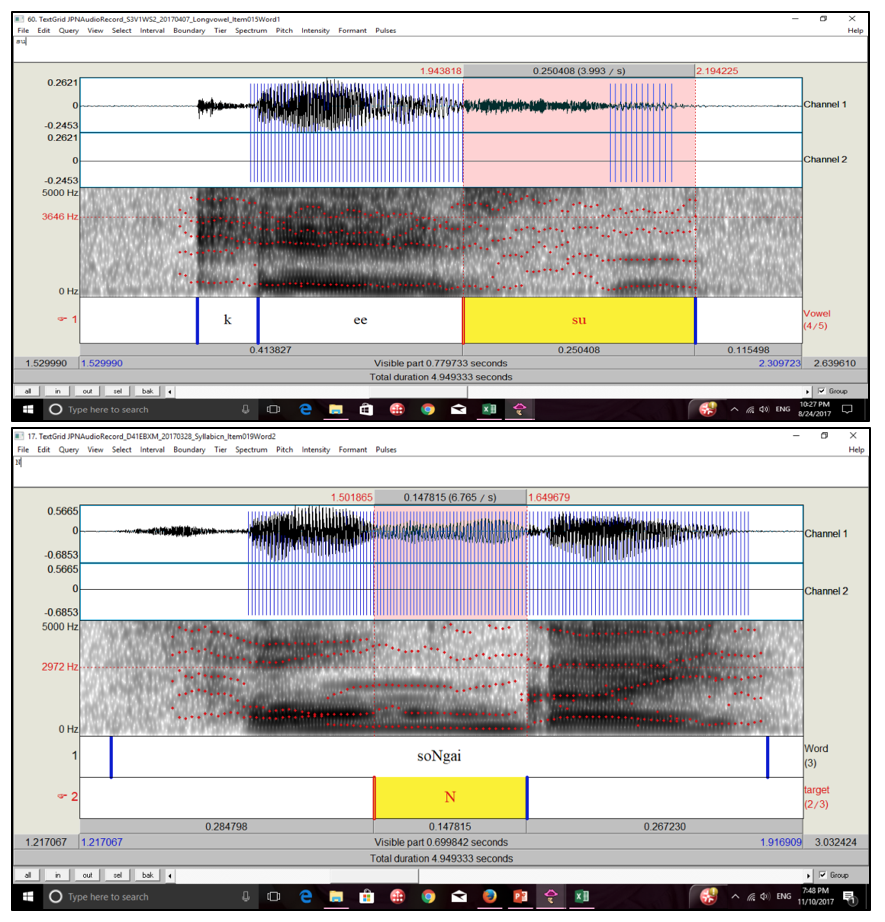

Vowel length contrast (V vs. VV)

Vowel length contrast (V vs. VV)